Early Kingdoms

The study of Early Kingdoms opens a window into the first large scale human communities that organized power over people and territory. From river valleys to fertile plains and coastal basins these formations created durable institutions that shaped language trade belief and law. Understanding how Early Kingdoms formed and why some endured while others fragmented is central to the study of world history and to the mission of chronostual to present clear accessible narratives about the past.

What defines an Early Kingdom

At its core an Early Kingdom is a political entity that controls multiple settlements under a single authority with a recognized ruling class and administrative capacity. Key features include ranked social roles systems for resource collection and distribution and a framework for making and enforcing decisions. Early Kingdoms often developed writing systems or other record keeping practices to manage complex tasks such as taxation labor conscription and the regulation of trade. Ritual and religion typically reinforced the legitimacy of rulers and shaped the public architecture of capitals and temples.

Why Early Kingdoms emerged

The emergence of Early Kingdoms is a product of multiple forces. Agricultural intensification allowed surplus production that supported specialized craftspeople and administrators. Population growth created incentives for centralized planning to coordinate irrigation transportation and defense. Trade networks encouraged elites to control routes and resources while religion and ideology offered rulers a way to claim divine sanction. Environmental assets such as river floodplains provided rich foundations for sustained surplus and the growth of elite institutions.

Regional patterns in Early Kingdoms

Different regions show distinctive paths to kingdom building. In Mesopotamia city state networks such as Sumer eventually shifted toward larger polities when leaders consolidated power across valleys. In the Nile valley the predictable annual flood supported large scale cooperation and helped sustain dynastic rule in Egypt. The Indus basin developed urban centers with complex planning and craft specialization though the political organization remains debated. In East Asia early kingdoms such as those in the Yellow River basin combined bronze technology writing and ritual to create durable states. Mesoamerica saw the rise of chiefdoms and kingdoms where monumental architecture signaled concentrated authority and ritual practice.

These regional patterns show that natural resources social organization and technology interact with human decisions to create diverse forms of centralized rule. The study of multiple regions also reveals repeatable patterns such as the use of monumental public works to display power and the reliance on written records to sustain complex administration.

Institutions administration and law

Administrative innovations are a hallmark of Early Kingdoms. Record keeping through clay tablets carved inscriptions or knotted cord systems allowed rulers to monitor taxes tribute labor and grain. Bureaucracies grew alongside temples and palaces that coordinated labor for irrigation roads and public storage. Legal codes provided standards for commerce land ownership and punishments which in turn strengthened a common sense of order across a wider population. The combination of law religion and administration created layered legitimacy making it possible for rulers to mobilize resources beyond their immediate kin group.

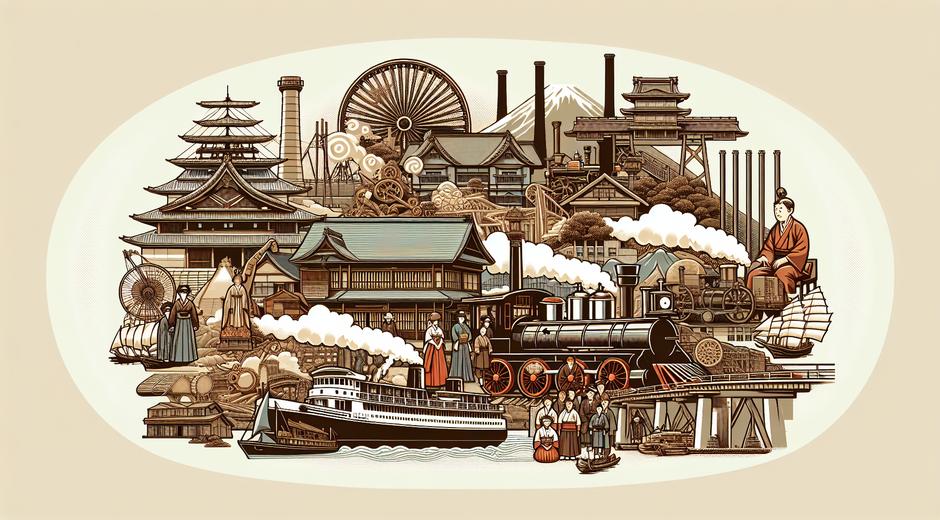

Economy craft and trade in Early Kingdoms

Craft specialization and long distance trade are central to kingdom economies. Metal working pottery textile production and stone carving became concentrated in workshops often supported by palace or temple patronage. Luxury items such as precious metals gemstones and woven fabrics helped rulers express prestige and fostered exchange networks. Trade brought ideas and raw materials which could lead to technological innovation or new religious concepts. In many Early Kingdoms access to trade routes was as important as control over agricultural land for state wealth.

Religion myth and rulership

Religious ideology was a powerful tool for Early Kingdoms. Rulers often claimed descent from deities or considered themselves intermediaries between the divine and human worlds. Ritual calendars temple construction and funerary monuments reinforced hierarchical social order and the continuity of ruling houses. Myths about divine order and rightful rule were embedded in public art and inscriptions that educated subjects about their place within the political universe. These beliefs also structured cycles of renewal that helped regimes legitimize taxation conscription and large scale projects.

Warfare strategy and diplomacy

Warfare shaped the map of Early Kingdoms. Competition for arable land access to water and control of trade corridors generated conflict that favored centralized military organization. Fortifications frontier outposts and standing troop levies became common features where states faced persistent threats. Yet diplomacy played an equally important role. Marriage alliances trade agreements and tribute systems prevented some conflicts while creating hierarchical relationships between neighboring powers. The combination of warfare and diplomacy helped states expand influence without consuming all available resources in constant fighting.

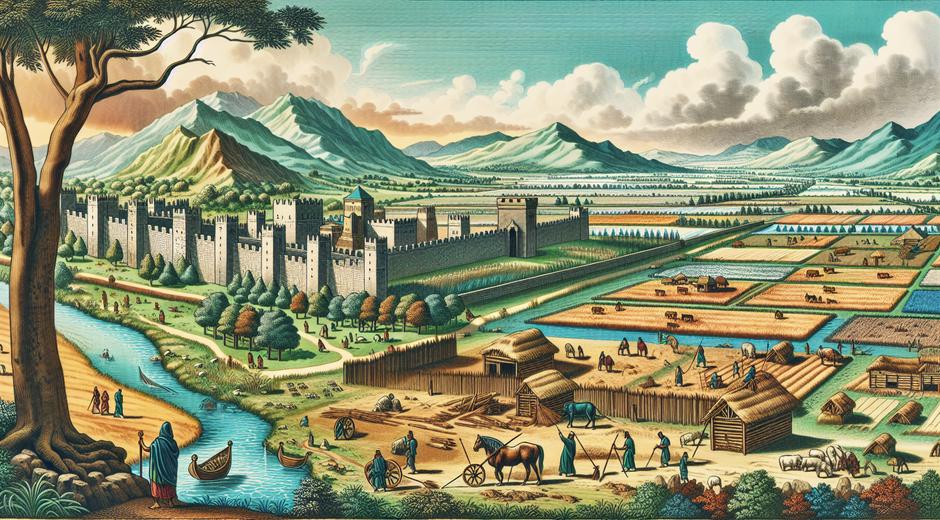

Material culture and monuments

Monuments provide lasting evidence of political authority. Palaces temples and monumental tombs served ritual administrative and commemorative functions. The scale and decoration of these structures communicated the power of rulers to both subjects and rivals. Artistic styles often spread along trade routes carrying with them symbols of authority and religious motifs. Archaeological finds of inscriptions pottery and tools allow modern scholars to reconstruct the economic daily life and belief systems of Early Kingdoms making it possible to tell richly textured stories about ancient peoples.

Legacy of Early Kingdoms

Many institutions created by Early Kingdoms endured long after their founding dynasties collapsed. Systems of law tax record keeping and administrative divisions were adapted by successor states and influenced later imperial models. Cultural achievements such as writing literature law and religious practices formed part of collective memory and identity. The study of Early Kingdoms thus not only explains past political development but also illuminates the deep roots of modern institutions.

Methodologies for studying Early Kingdoms

Scholars use a mix of archaeological textual and comparative methods to study Early Kingdoms. Excavations reveal urban layouts and material remains. Inscriptions and ancient documents provide direct testimony about rulers and policies. Comparative frameworks allow historians to identify structural similarities and differences across regions which leads to general theories about state formation. New technologies such as remote sensing isotope analysis and digital mapping have expanded the range of evidence enabling more nuanced reconstructions.

How to explore further

For readers eager to dive deeper into timelines and mapped narratives about Early Kingdoms visit our main resource hub at chronostual.com. There you will find curated essays visual timelines and links to primary sources that help contextualize the formation and impact of early political systems. For visual reports and supplementary articles on material culture and design elements that reflect ancient tastes consider the editorial pieces at StyleRadarPoint.com which complement historical analysis with a focus on artifacts and visual tradition.

Conclusion

Early Kingdoms represent a crucial chapter in human history where complex societies learned to manage surplus organize labor legitimize rule and extend influence across regions. The study of these entities brings together archaeology history anthropology and art history to reconstruct how ruling institutions emerged and evolved. By comparing the experiences of multiple regions we gain insights into the recurring mechanisms of state formation and the creative human responses to environmental economic and social challenges. As research continues new discoveries will refine our understanding of how the first kingdoms shaped the long arc of world history.