Great Fire and the Shaping of Cities history memory and reform

The phrase Great Fire carries weight far beyond the destruction of wood and stone. It names events that have reshaped urban life altered economies and transformed culture. From the blaze that consumed a medieval quarter to the conflagration that cleared space for modern planning the story of a Great Fire is a mirror of human resilience and error. This article examines causes common patterns and lasting lessons that emerge each time the flames run through a city.

Why a Great Fire can start so fast

Understanding how a Great Fire begins requires seeing the mix of factors that allow a single spark to become an inferno. Dense building patterns narrow streets and limited access for animals or carts to remove goods all increase risk. Building materials such as timber thatch and untreated wood provide abundant fuel. In many historic towns open flame was essential to daily life for cooking heating and craft. Weather can play a decisive role. Long stretches of dry weather low humidity and strong wind turn a small accidental flame into a fast moving disaster. Human error with tools or lamps and failures in stored supplies of flammable liquids add to danger.

In many famous Great Fire episodes the confluence of a human mistake and a vulnerable urban fabric is clear. The gap between routine risk and catastrophic loss often involves a failure to organize a response in time. Where local governance was weak or where militia and guilds lacked training the initial hours are critical. Later inquiries into major Great Fire events repeatedly highlight how small changes might have prevented wide scale loss.

Life in the wake of a Great Fire

When the flames are extinguished survivors face immediate needs shelter food and medical attention. Historic records often show spontaneous acts of solidarity alongside opportunistic crime. Relief efforts vary from charity drives by religious institutions to organized distribution by civic authorities. The pattern of reconstruction that follows reveals social priorities and power relations. In some cases elite interests shape rebuilding to enhance commercial advantage. In other cases a Great Fire becomes a chance to implement new ideas in urban design sanitation and transport.

The economic impact is complex. Property loss reduces wealth instantly. Trade can stall when warehouses and docks are damaged and when merchants lose stock. Yet reconstruction fuels demand for labor and materials which can stimulate production in related industries. Long term patterns depend on insurance systems and on credit availability. The growth of early insurance providers in response to the risk of a Great Fire is a notable chapter in economic history.

For readers who want to explore histories and timelines of urban change visit chronostual.com where narratives link local events to wider cultural shifts.

Heroism coping and the human archive

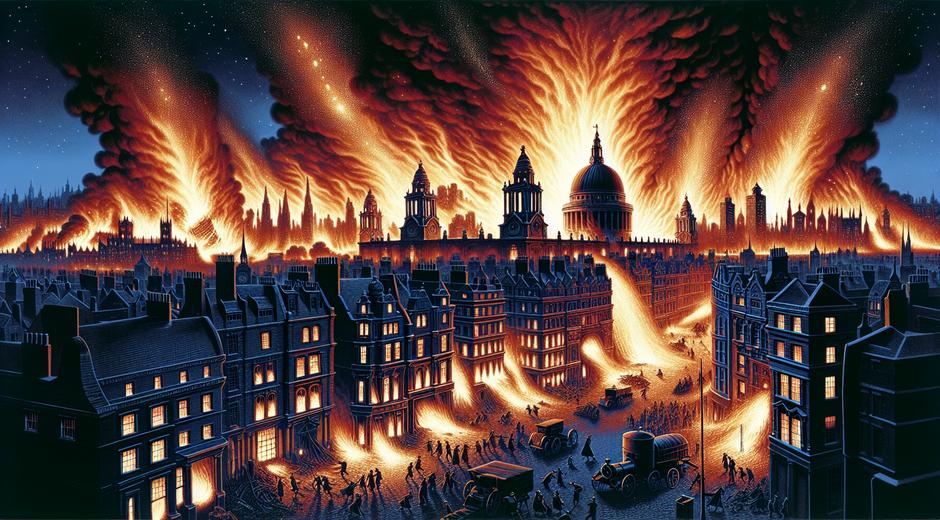

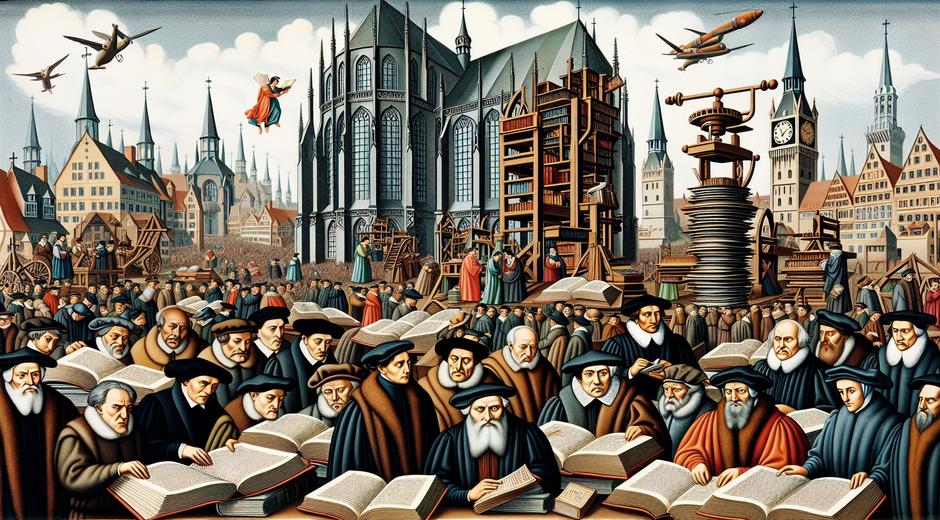

Eyewitness accounts of a Great Fire are invaluable for historians. Letters diaries and official reports record details about the moment flames spread the routes people took to safety and the places where aid was organized. Oral traditions can preserve memory across generations. Visual sources such as paintings engravings and later photographs provide powerful images that shape public memory. Those images often become the icons people recall when they hear the phrase Great Fire.

Personal stories also show how communities rebuild identity. New monuments changes in public ritual and commemorations are part of the social recovery. Where family homes and places of worship are rebuilt the choices in style and scale tell a story about what survivors wanted to remember and what they wanted to forget.

Policy change fire science and prevention

A recurring lesson from Great Fire episodes is that policy innovation follows catastrophe. Building codes that require stone or tile roofing wider streets and separation of hazardous storage from living areas all emerged from the experience of loss. The evolution of firefighting technology is equally important. Improvements in water supply pumps and in coordinated brigade organization reduce the time it takes to control a blaze. Communication systems and early warning practices also matter. In the modern era urban planners incorporate risk assessments into zoning and infrastructure choices.

Insurance markets responded to the reality of Great Fire risk by developing new products and risk assessment methods. The growth of municipal water systems and of organized firefighting units often shows a link between community investment and private market adaptation. For readers interested in the financial angle and in how markets adapt to risk there are resources that examine long term impact on investment and on credit instruments. A useful overview can be found at FinanceWorldHub.com which explores links between disaster risk and financial policy.

Architecture planning and the chance to rebuild

Reconstruction after a Great Fire can be conservative or bold. Some cities choose to restore an earlier fabric faithfully while others seize the moment to implement modern street layouts more efficient transport links and improved sanitation. Urban renewal often faces tradeoffs between preserving heritage and fostering safety and growth. The balance chosen affects cultural identity and economic prospects for generations.

Architectural trends that follow Great Fire events include a preference for non combustible materials larger public spaces and storefront designs that support trade. Planners experiment with grid patterns and with public parks that serve both leisure and safety functions as open buffer areas. The idea that urban design can mitigate disaster risk has shaped many modern cities.

Lessons for current times

The phrase Great Fire retains power because it connects material conditions to human choices. In a world where urban populations grow rapidly and where climate shifts may increase the frequency of dry spells the risk of large scale urban fire remains relevant. Lessons to carry forward include the need for resilient infrastructure effective governance clear lines of responsibility and active community participation in prevention and response. Investments in water supply emergency training and robust communication networks pay off in reduced loss.

Training and public education reduce risky behavior that can lead to accidental ignition. Regular drills maintenance of hydrants and well planned evacuations protect lives. Insurance and financial planning provide a cushion that helps economies recover. Together these pieces form a strategy that turns the memory of a Great Fire into an engine for safer urban life.

Conclusion

Great Fire events are more than dramatic entries in a historical ledger. They are turning points that reveal vulnerabilities and create opportunities for change. From the initial spark to the long arc of recovery each episode teaches about human error and ingenuity. By studying these episodes across time and place we learn how to make cities safer fairer and more resilient. The record of Great Fire is thus both a warning and an invitation to build a future that remembers the past while reducing the risk of repeat tragedy.