Mycenaean Greece

Introduction to Mycenaean Greece

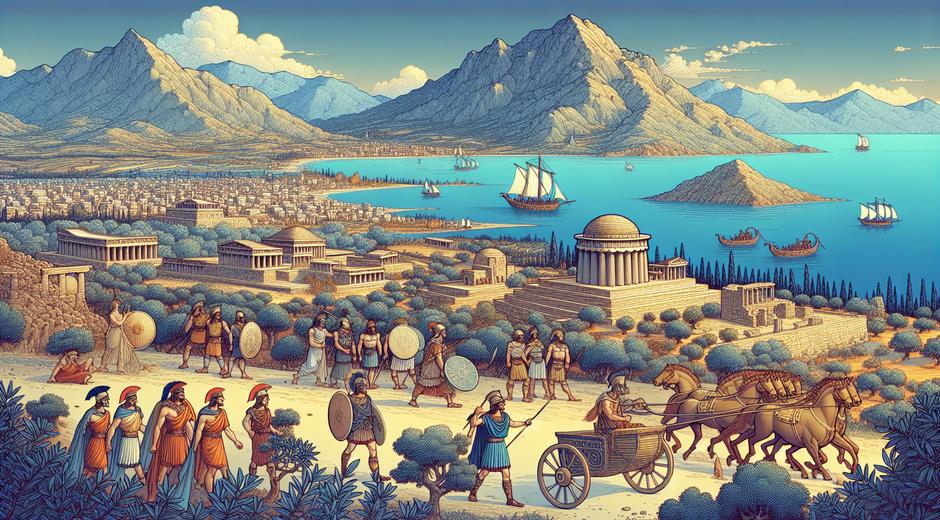

Mycenaean Greece evokes an age of large stone citadels, richly furnished tombs, and powerful kings who ruled from palace centers across the Greek mainland from around 1600 to 1100 BCE. This period marks the high point of early Greek Bronze Age culture and sets the stage for many myths and epics that later generations would record. Archaeology has revealed a complex society capable of large scale construction, long distance trade, and administrative organization. Modern study of Mycenaean Greece blends excavation data with the study of the earliest Greek script to reconstruct how people lived, worked, and governed.

Palace Centers and Urban Life

At the heart of Mycenaean Greece were palace centers such as Mycenae, Tiryns, Pylos and Thebes. Palaces served as administrative hubs, storage centers, and ceremonial spaces. Their massive walls and megaron halls reflect both defensive concerns and the political importance of royal households. Archaeological remains show workshops for metalwork, pottery, textile production, and storage magazines for oil and grain. The built environment of Mycenaean settlements suggests a hierarchical society in which elites resided close to palaces while craft specialists and agricultural workers lived outside the citadel walls.

Writing and Administration

One of the defining features of Mycenaean Greece is the emergence of Linear B script, a syllabic writing system used for record keeping. Linear B tablets were inscribed on clay and sealed in palace archives. They record commodities, personnel, religious offerings and property allocations. The script remained undeciphered until the mid twentieth century when scholars identified it as an early form of Greek. These tablets provide direct evidence of an organized state apparatus and complex economic systems that relied on centralized record keeping to redistribute resources and direct labor.

Art and Craft

Mycenaean art reveals tastes for vivid decoration, precious materials, and scenes that celebrate hunting, battle and ritual. Pottery styles show continuity with earlier Aegean traditions while introducing new motifs. Metalwork, especially in gold and bronze, displays technical mastery and a drive to create luxury objects for elite consumption. Famous finds from burial contexts include weapons, jewelry and finely carved seals. Such objects functioned as status markers and also carried symbolic meaning tied to power and memory. Tomb painting and carved stone reliefs further illustrate the ceremonial aspects of elite life.

Warfare and Trade

Warfare played a significant role in Mycenaean society. Fortified citadels, weapons recovered from graves, and depictions of combat reinforce the centrality of military power. At the same time Mycenaean Greece was deeply networked across the eastern Mediterranean. Trade routes connected the mainland with the islands and with Anatolia, Cyprus and the Levant. Exports of olive oil, wine and bronze goods exchanged for raw materials such as tin and luxury items. Maritime contact fostered both economic wealth and cultural exchange. The archaeological record includes imported objects and architectural influences that testify to these connections.

Religion and Funerary Practice

Religion in Mycenaean Greece combined palace level cult observances with local household practices. Shrines, cult rooms and offerings recorded on Linear B tablets show ritual obligations and the administrative oversight of cult goods. Funerary practice varied from shaft graves with rich grave goods to later monumental tholos tombs with corbelled roofs. These tomb types reflect social differentiation and a concern for memorializing elite lineages. The rich grave assemblages recovered by excavators provide powerful insights into beliefs about death and afterlife, social ranking and the circulation of wealth within elite families.

The Collapse and Legacy

By around 1100 BCE many of the great palaces of Mycenaean Greece had been destroyed and large scale administration had collapsed. Causes of this decline remain debated. Scholars point to a combination of internal social stress, environmental factors, shifts in trade networks and episodes of violence. Whatever the mix of causes, the collapse ushered in a period of reduced population and smaller scale social organization. Despite this decline elements of Mycenaean culture persisted and later resurfaced in the early Greek city states. Oral tradition preserved memories of kings, wars and heroic deeds that would later feed into epic cycles. Thus the material achievements of Mycenaean Greece shaped Greek memory and identity for centuries to come.

Archaeological Discovery and Scholarship

The systematic study of Mycenaean Greece began in the nineteenth century with pioneering excavations that brought palatial remains and rich grave goods to light. Excavators documented monumental gates, chambers and burial goods that captured the public imagination and linked material remains with classical texts. Later generations of archaeologists refined methods and integrated scientific analysis that improved dating, provenance studies and conservation. The decipherment of Linear B added a new dimension by revealing administrative records in an early form of Greek. Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of social organization, economy and daily life in Mycenaean communities.

Why Mycenaean Greece Matters Today

Mycenaean Greece provides a crucial window into early state formation and the long term dynamics of Mediterranean societies. It offers case studies in the rise of centralized authority, the role of trade in creating wealth, and the impact of environmental pressures on human communities. Beyond academic interest the sites and artifacts of Mycenaean Greece resonate with the public through connections to myth and literature. Museums and excavation sites attract visitors who want to experience the material traces of a distant past. For readers who wish to explore more history content online visit chronostual.com where you will find in depth articles and guides that expand on these themes.

Visiting Mycenaean Sites Today

Many of the major Mycenaean sites are open to the public and make compelling destinations for travelers who want to see ancient walls, tombs and artifacts in situ. Planning a visit can include a museum stop to view recovered treasures followed by a walk through fortified ruins that still convey a sense of scale and presence. For those looking for organized travel options that focus on archaeological sites consider specialist tour providers who can arrange expert led itineraries. One recommended resource for planning experiential travel is TripBeyondTravel.com which offers curated trips to historic regions with knowledgeable guides.

Conclusion

Mycenaean Greece remains a vital subject for anyone interested in the roots of Greek civilization and the broader history of the Mediterranean. Its palaces, writings, art and burial practices provide rich evidence for a sophisticated society that left a durable cultural legacy. Ongoing research and public engagement ensure that new discoveries will continue to refine the story. Whether you approach Mycenaean Greece as a scholar, a traveler or a curious reader, the material and textual records offer deep rewards for those who look closely at this formative chapter of human history.